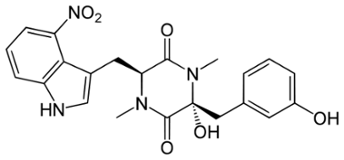

Thaxtomin A, a phytotoxin produced by Streptomyces eubacteria, is suspected to act as a natural cellulose synthesis inhibitor. This view is confirmed by the results obtained from new chemical, molecular, and microscopic analyses of Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings treated with thaxtomin A.

Thaxtomin A, a phytotoxin produced by Streptomyces eubacteria, is suspected to act as a natural cellulose synthesis inhibitor. This view is confirmed by the results obtained from new chemical, molecular, and microscopic analyses of Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings treated with thaxtomin A. Cell wall analysis shows that thaxtomin A reduces crystalline cellulose, and increases pectins and hemicellulose in the cell wall. Treatment with thaxtomin A also changes the expression of genes involved in primary and secondary cellulose synthesis as well as genes associated with pectin metabolism and cell wall remodelling, in a manner nearly identical to isoxaben. In addition, it induces the expression of several defence-related genes and leads to callose deposition. Defects in cellulose synthesis cause ectopic lignification phenotypes in A. thaliana, and it is shown that lignification is also triggered by thaxtomin A, although in a pattern different from isoxaben. Spinning disc confocal microscopy further reveals that thaxtomin A depletes cellulose synthase complexes from the plasma membrane and results in the accumulation of these particles in a small microtubule-associated compartment. The results provide new and clear evidence for thaxtomin A having a strong impact on cellulose synthesis, thus suggesting that this is its primary mode of action. Cellulose is the major component of the plant cell wall (CW). The CW provides general plant strength and is important for the protection of cells against pathogens, dehydration, and other environmental factors. In addition, the primary CW contributes to the determination of plant development, cell shape, and cell cell interactions. Once expansion growth has ceased, some cell types deposit a thick secondary CW, which is mainly composed of highly aligned, crystalline cellulose and xylans, and which can also be lignified in order to provide further strength. Defects or irregularities in cellulose deposition and CW integrity have been shown to trigger defence pathways in both primary and secondary CW mutants. Synthetic chemical compounds, for example, isoxaben or dichlobenil (DCB), that specifically inhibit CW synthesis have been identified previously. Pinpointing such a compounds molecular and cellular effects on CW synthesis and identification of the genetic modifications in mutants resistant or hypersensitive to such compounds can advance our understanding of CW biology. Genetic studies revealed that the herbicide isoxaben has a direct effect on cellulose synthases (CESA), i.e. CESA3 and CESA6 as well as CESA2 and CESA5. Isoxaben has also been reported to prevent incorporation of glucose into the CW and to inhibit the assembly of hemicelluloses. More recently, isoxaben and DCB were also shown to cause aberrant CESA complex (CESA-C) patterns in the plasma membrane (PM) by changing CESA motility and to affect cortical microtubule arrays. The cyclic dipeptide thaxtomin A is the only somewhat familiar natural compound for which inhibition of cellulose synthesis has been suggested. Thaxtomin A is produced by plant-pathogenic soil bacteria of the genus Streptomyces implying that cellulose synthesis is a natural target in plant pathogen interactions. The molecular mode of action of thaxtomin A remains unknown. It was noted that nanomolar concentrations of thaxtomin A cause swelling of hypocotyls and reduced seedling growth in A. thaliana. In tobacco suspension cultures, it causes radial cell swelling in dividing or expanding cells, but does not affect mitotic and cortical microtubules. Thaxtomin A also inhibits normal cell elongation of tobacco suspension cells in a manner that suggests an effect on primary CW development, and the incorporation of [14C]-glucose into the acid-insoluble CW fraction (i.e. cellulose) in A. thaliana hypocotyls. Furthermore, etiolated A. thaliana seedlings treated with nanomolar concentrations of thaxtomin A display a Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectral phenotype that is most related to those of A. thaliana rsw1/cesa1 mutant seedlings or A. thaliana seedlings treated with cellulosesynthesis inhibitors like DCB, isoxaben, or flupoxam. In addition to thaxtomin A has putative role as a cellulose synthesis inhibitor, its application to plants was proposed to trigger an early Ca2+ signalling cascade that might be crucial for plant-pathogen interactions. However, although thaxtomin A leads to programmed cell death, no evidence for an activation of defence responses like oxidative burst, rapid medium alkalization or an activation of defence genes has been reported.

Thaxtomin A affects CESA-C abundance and motility. (A, B) Optical sections of plasma membrane in upper hypocotyl cells of 3-d-old etiolated cesa3:GFP-CESA3 seedlings. Images were acquired by spinning disc confocal microscopy. Average projections of 39 and 54 frames acquired in 15 s intervals in the plane of the cell membrane of control (A) and thaxtomin A-treated seedlings (B), respectively are shown. Average projections illustrate the movement of labelled particles along linear tracks. (C) Kymograph of the region marked by the dotted line in (A) displaying steady and bidirectional particle translocation. (D) Kymograph of region marked by the dotted line in (B) displaying steady, slow, accelerated or very fast particle translocation. (E) Box plot diagram of particle velocities calculated from 140 or 300 particles of control or thaxtomin A-treated seedlings, respectively. Particle velocity was measured in six cells from four seedlings and was determined by manual tracking.

Sources: (Shedletzky et al., 1992) (Braam, 1999; Vorwerk et al., 2004) (Turner et al., 2001) (Delmer and Amor, 1995) (Ebringerova and Heinze, 2000; Brown et al., 2005) (CanËœo-Delgado et al., 2000; Ellis et al., 2002; Hernandez-Blanco et al., 2007) (King et al., 2001; Fry and Loria, 2002; Scheible et al., 2003) (Desprez et al., 2007) (Hogetsu et al., 1974; Heim et al., 1990) (Lazzaro et al., 2003; Paredez et al., 2006, 2008; DeBolt et al., 2007) (Scheible et al., 2003; Robert et al., 2004) (Tegg et al., 2005) (Duval et al., 2005) (Fry and Loria, 2002) (Scheible et al., 2003) (King and Lawrence, 1996) (Scheible et al., 2001; Desprez et al., 2002) (Scheible et al., 2003) (Heim et al., 1990, 1998) (Paredez et al., 2006; DeBolt et al., 2007)